Testing Minimalism in Practice

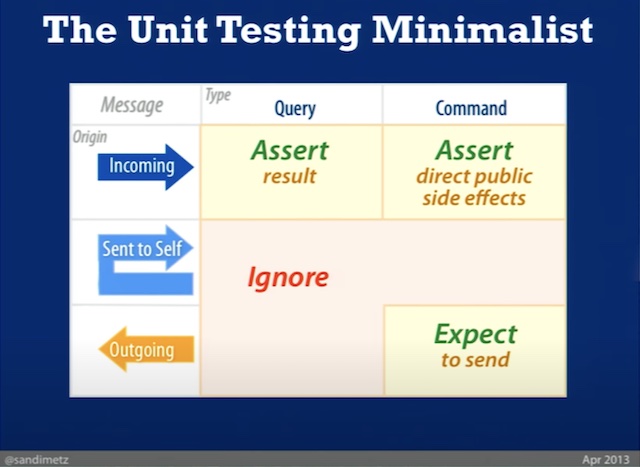

One of the most paradigm shifting ideas I've encountered in my career is Sandi Metz's description of Unit Testing Minimalism. In her RailsConf talk, The Magic Tricks of Testing, she shares a simple diagram entitled: The Unit Testing Minimalist.

or

| Message | Query | Command |

|---|---|---|

| Incoming | Assert result | Assert direct public side effects |

| Sent to self | Ignore | Ignore |

| Outgoing | Ignore | Expect to send |

I refer to this diagram frequently and apply it to every type of test. Hence the title of this post beginning with “Testing” rather than “Unit Testing”.

I can’t remember exactly where I heard her say this, maybe in the above mentioned talk, but Sandi once said something like “Most developers write too many tests.” I have found this to be completely true. In the past, I certainly wrote too many tests.

My motivation for writing about this is due to the assertions I encounter when reviewing others’ code (I’ll go ahead and throw all of my old code in there, too).

Note: There’s nothing I’ll share here that Sandi hasn’t already expressed way better than I could. If you don’t continue reading, I’d highly encourage you to at least watch her talk.

Examples

I want to share 3 of the common examples I see where there are too many tests:

- Asserting object state.

- Asserting the behavior of 3rd party dependencies.

- Repeating assertions.

I’ll be using some pseudo testing code throughout these examples. They aren’t intended to be copied/pasted for any reason.

Object State

Asserting an object’s state is pointless but I see it all the time. The state of an object may imply correctness in your application but it doesn’t guarantee it. To be fair, I don’t often see these assertions in unit tests but do see them in a lot of integration and acceptance tests.

I often see this type of issue with components or views that communicate with a parent component, controller or service.

Here’s an example involving a product component and a shopping cart:

test('it can add a product to the cart', function() {

const cartService = lookupService('cart');

expect(cartService.numItems).toEqual(0);

visit('/products/test-product-1');

click('.add-to-cart');

expect(cartService.numItems).toEqual(1);

visit('/cart');

const products = findAll('.cart-item');

const [product] = products;

expect(products.length).toEqual(1);

expect(product.find('.cart-item-name')).toEqual(

'Delicious Chocolate Bar'

);

// etc.

});This is a particularly egregious example but the point is to make it easier to see the flaw. We’re asserting that some cart service state—the number of items within—has increased by one because we clicked the add to cart button.

This implies that our application is behaving correctly but it doesn’t guarantee anything. It doesn’t tell us if the item was added to the cart correctly or if our cart service is even in use.

There are 2 better approaches here, depending on the type of test:

- If we’re writing an acceptance test, we should assert the public side effect.

- If we’re writing a rendering or component test, we should assert that our component sends the right data.

An acceptance test example:

test('it can add a product to the cart', function() {

visit('/products/test-product-1');

click('.add-to-cart');

visit('/cart');

const products = findAll('.cart-item');

const [product] = products;

expect(products.length).toEqual(1);

expect(product.find('.cart-item-name')).toEqual(

'Delicious Chocolate Bar'

);

// etc.

});Note: We can write assertions for each attribute of our product we want displayed on the cart page but similarly fine approaches would be to take a snapshot (visual or of the DOM) and assert the snapshots match our expectations.

In the above example we don’t assert anything about the cart service at all, let alone its state. We could swap out the cart service with something else entirely and as long as our products can be added to the cart, our test will pass.

We’re also ensuring the action we took on the product page as a user results in the correct cart page as a user would see it.

A rendering test example:

describe('Component | Product Card', function() {

test('it can add a product to the cart', function() {

const mockCartService = {

addItem: createMockFn()

};

render(

<ProductCard cart={mockCartService} product={mockProduct} />

);

click('.add-to-cart');

expect(mockCartService.addItem).toHaveBeenCalledWith(mockProduct);

});

});In the above example, we don’t worry about wiring up our actual cart service or asserting anything about its state. What we want to assert is that our product card component sends the right message to the cart service. What the cart service does with the product data we send it is beyond the scope of our component.

3rd Party Dependencies

A bit similar to the idea of testing object state, I also often see code that asserts something about the state or behavior of a 3rd party dependency.

Note: I’m including things like backend servers in the term “3rd party dependencies”.

I’ve seen the temptation to mock or assert 3rd party dependencies result in a couple of common patterns:

- Implementing complex server-side behavior when mocking calls to external services.

- Asserting the behavior of objects in a library or framework dependency.

Mocking Server-side Behavior

In nearly every project I’ve worked on, Mirage JS has been used to intercept network requests in acceptance tests and return mock responses that match the data structures returned from real servers.

I’ve been asked many times how to implement filtering and sorting with Mirage by fellow developers trying to test things like search pages. I should note: I’m not against adding this behavior when using Mirage in development, e.g., to demo a realistic prototype.

I understand how easy it is to think about adding this behavior in a testing context but it doesn’t add value, only complexity and the headache of writing your own server-side logic. If you’re in the mindset of “I’m mocking my server” then it’s easy to assume you need to mock every type of interaction with it.

If we think of a search page as a unit, and apply the rules of the Unit Testing Minimalist, we realize we only need to assert the outgoing command: “Sort this” or “filter this”. What the server does with that information is beyond the scope of our search page.

Similarly, we can mock special cases, e.g., an empty search result, without implementing a fully functioning mock server. Instead of writing a test that does something like:

mock results

- render search page

- apply filter

- assert filter was sent

- apply filter logic

- receive empty result set

- assert special messagingWe can write two tests and avoid implementing any filtering logic:

# test 1

mock results

- render search page

- apply filter

- assert filter was sent

# test 2

mock empty results

- render search page

- assert special messagingDependency Behavior

Another common case I encounter involves asserting the behavior of 3rd party application dependencies. I think this typically comes from developers who are just starting out with testing and don’t yet know when they’ve crossed the boundary of their concerns.

An example would be testing the state or behavior of a 3rd party datastore. If I have one of these dependencies in my application, I should be sure it’s already well tested. If not, I should probably not depend on it.

The testing boundary, in this case, is the point in your code where you send a message to the datastore. In your tests, mock the datastore and assert that you’re sending it the right information. Beyond that, trust that is does what it’s supposed to do.

An example of what not to test:

describe('Unit | User Form', function() {

test('it can update the user data', function() {

const thirdPartyStore = new ThirdPartyStore();

render(

<UserForm store={thirdPartyStore} user={mockUser} />

);

fillIn('.first-name', 'Bob');

click('.submit-button');

expect(

thirdPartyStore.find('user', mockUser.id).firstName

).toEqual('Bob');

});

});This is too much and it couples the test code directly to the datastore dependency. It would be nice to be able to swap out one datastore for another, without breaking your tests.

A better way to test:

describe('Unit | User Form', function() {

test('it can update the user data', function() {

const mockStore = {

update: createMockFn()

};

render(

<UserForm store={mockStore} user={mockUser} />

);

fillIn('.first-name', 'Bob');

click('.submit-button');

expect(mockStore.update).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

firstName: 'Bob'

});

});

});Here, we assert that our component sent the right message to the store. We don’t need to test the internal state of the store.

Note: An even better approach would be to proxy the 3rd party datastore in your own codebase. This way, you can have a consistent store interface in your application, even if you swap out the datastore dependency and its own interface changes.

Repeat Assertions

This is definitely a smaller issue but one I see all the time. Maybe it’s often a case of careless copy/paste but, more seriously, it could be a sign that a developer doesn’t understand the tests they’re writing.

I often see this in acceptance tests: Repeated assertions that visiting a route in the application results in the correct URL.

They often look like this:

describe('Acceptance | Profile Page', function() {

test('it displays confirmation on save', function() {

visit('/profile/1');

expect(currentURL()).toEqual('/profile/1');

click('.edit-button');

fillIn('.first-name-input', 'Bob');

click('.save-button');

expect(find('.save-modal')).toBeVisible();

});

test('it transitions to delete confirm page', function() {

visit('/profile/1');

expect(currentURL()).toEqual('/profile/1');

click('.delete-button');

expect(currentURL()).toEqual('/profile/1/delete');

});

// …and so on, etc.

});Each test asserts that visiting a given URL results in the correct URL. This is to ensure no routing issues or redirects to error pages are occurring.

I would argue that these assertions likely aren't needed at all. If you’re testing unique features of a page in your app, the tests will fail if you end up on the wrong page.

That said, it’s totally fine to have these assertions but not in every test. In this scenario, there’s a missing test. The solution is to extract the current URL assertion to its own test and remove it from all the others.

test('it renders the correct URL', function() {

visit('/profile/1');

expect(currentURL()).toEqual('/profile/1');

});I hope you’ve found the topic of testing minimalism interesting. Have you realized you may have too many tests? Are there other patterns you’ve seen that could benefit from some testing minimalism? Feel free to let me know.