Better Code Reviews by Example

The goal of this post is to provide some concrete examples of code review improvements but really this is about improving communication.

Namely:

- Be clear and direct (not to be interpreted as “be blunt” or “be rude”)

- State your intentions (and assumptions)

- Speak from your perspective

- Let things go or put a pin in them

Poor communication during code review can waste time or even degrade the relationship between pull request (PR) author and reviewer.

The problems highlighted in this post run the risk of an author ignoring feedback entirely or feeling antagonized by a reviewer. Either case can lead to an author avoiding a reviewer in the future or feeling unsafe opening new PRs.

Note: No judgement is intended for any PR reviewers out there. Most of the observations I’m sharing in this post have come from my own experiences giving feedback and learning how to get better.

Be Clear and Direct ^

Clear and direct feedback is important for saving time, teaching and building trust. There’s no place for rudeness, however, or character assassination. Every developer makes mistakes and has room to learn new things.

Below are a few examples where being more clear and direct can improve feedback:

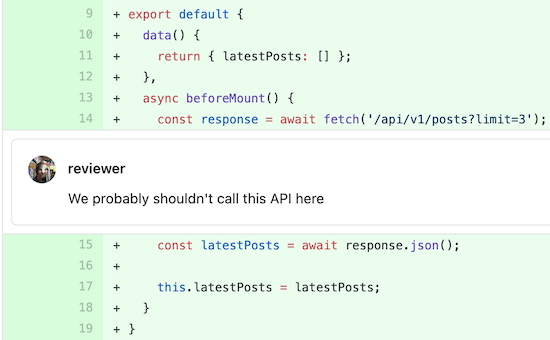

Problem: Being Vague

Vague feedback can be frustrating, especially if an author feels they can’t ignore it, e.g., if the feedback comes from a very senior team member. Sometimes a reviewer’s intention is to start a conversation but that can be really unclear and it still puts a burden on the author to figure out what to do.

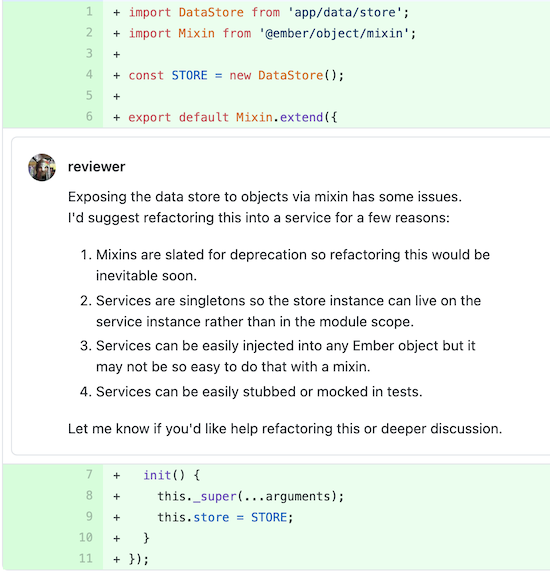

In the above example, the feedback has several problems.

- The word “probably” makes it hard for the author to understand if the change is important or necessary but it’s likely the reviewer is definitely asking for a change. It could be that the reviewer is trying to be nice and take a softer approach but that probably won’t come across to the author.

- There’s no indication of what the reviewer thinks should be done instead. It could be that the reviewer wants to start a conversation but this isn’t obvious. In the worst cases, authors take vague feedback and try to refactor their code without telling anyone. This often leads to new, different problems.

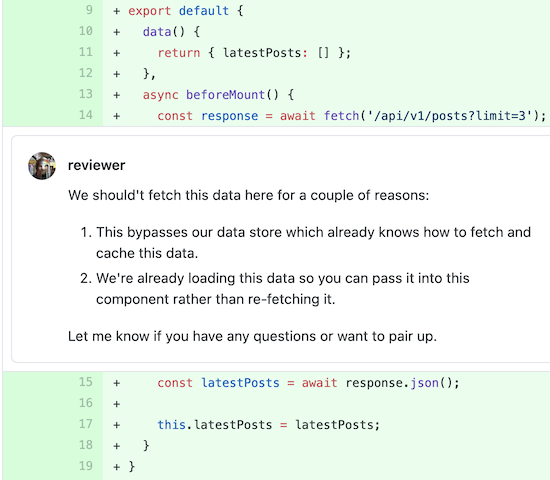

An example of more clear feedback:

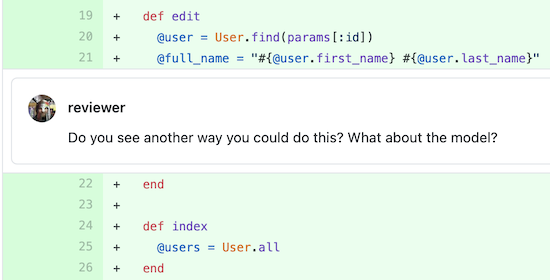

Problem: Dropping Hints

I’ve seen a lot of reviewers hint at the code changes they’d like to see from authors. This can be ok, especially if the reviewer and author have agreed to this style of communication; however, unsolicited hints often feel patronizing. If some hints go over an author’s head, time gets wasted seeking clarification.

I can understand the temptation to leave hints, you don’t want to take away someone’s opportunity to figure things out for themselves, but unless they specifically ask for hints, this is a big assumption. When in doubt, there’s no harm in asking: “Would you prefer if I give you hints about code changes or just ask for them directly?”

An example of feedback without any hints:

Problem: Indirection

Indirect or implicit feedback about code changes puts a burden on an author to interpret the desired outcome from the reviewer. It’s easy for reviewers to accidentally communicate around code problems.

Often, reviewers suggest solutions without identifying problems. Note: People who solve problems for a living tend to do this in many settings, not just during code review.

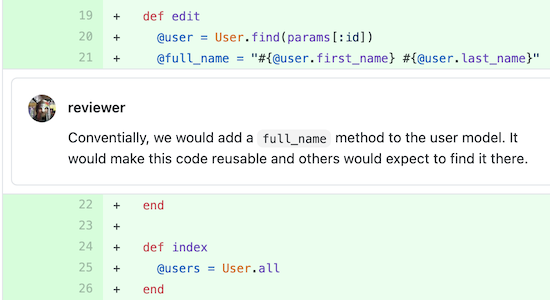

An example of more direct feedback which outlines some problems:

Side Effects

Another case can happen when a reviewer recognizes an issue with a code change and starts thinking about side effects. It can be easy to focus on those side effects and communicate about them instead of the underlying problem, e.g., “These code changes lower our code quality score.”

Instead of communicating about the code quality score, which implies some problematic code, a reviewer should identify the questionable code and teach a higher quality alternative to the author.

Teach, Don’t Tell

As a reviewer, you should avoid dogma and, when possible, teach the reasoning behind your feedback. Telling an author which changes to make may result in the code you want but runs a big risk of teaching them nothing and resulting in the same or similarly uninformed decisions in the future.

I find the best teaching comes directly from experienced team members. If you can clearly and concisely explain why an author should change their code, they get a lot of valuable knowledge quickly.

Directing authors to articles, documentation, Google, or even books, places a time-consuming burden on them and runs the risk that they won’t derive the knowledge you expect them to after consuming the material.

That said, it should be totally fine to share a resource that teaches something perfectly. If you can say “This article perfectly captures my thoughts” or “I couldn’t say it any better myself” then the resource is probably ok to share as long as the connection to the code changes and outcome you’d like is clear.

State Your Intentions and Assumptions ^

If you don’t know what other people intend by their words and actions, you can only guess. If you’re playing the role of reviewer, it really helps to state your intentions. I like to qualify my feedback by stating how I intend it to be received.

When I don’t think the author necessarily needs to make code changes, I often find myself starting out some feedback with “This is not a blocker…”, “This is take it or leave it…” or “Don’t feel the need to change this unless you want to…”

With more critical feedback, I aim for the same level of clarity, e.g., “This code introduces a bug…”, “This can’t be merged until…”, etc.

Note: In either case, the ”Teach, Don’t Tell“ approach should still apply.

Flipping things around, I also find it very helpful to state your assumptions. As a reviewer, if you don’t know the author’s intentions, you can only guess. A lot of time gets wasted when a reviewer assumes an author’s intent or goals and asks for changes based on that assumption. A lot of back and forth discussion ensues while not being on the same page.

“I assume you’re trying to solve x problem with y solution. In that case, I’d like to suggest…

Starting some feedback with something like “I assume you’re trying to solve x problem with y solution. In that case, I’d like to suggest…” is a great way to avoid misunderstandings early. If you state your assumptions up front, and they’re incorrect, the author can clear things up right away and avoid wasteful back and forth discussions.

Speak From Your Perspective ^

This may not seem obvious but many of us communicate from others' perspectives. You may find yourself advocating for your teammates or users or all developers in general without realizing it.

This can become a conversation blocker during code review if you as a reviewer communicate from a perspective other than your own and an author disagrees with your interpretations.

For example, a comment like “The team would have a hard time maintaining this code” is subjective and debatable. What‘s often the case is that these types of statements are true for the person saying them.

“I have a hard time understanding this code.

Better feedback would describe the problem from the reviewer’s perspective, e.g., ”I have a hard time understanding this code.” When we speak from our own perspectives, there’s no room for debate and thinking this way can actually reshape our thoughts and clarify the feedback we want to give.

Let Things Go or Put a Pin in Them ^

This section is about the small things. You shouldn’t let bugs, vulnerabilities or similarly large issues go or put a pin in them.

Time permitting, I personally feel it’s ok to nitpick code changes. If an author can make changes in a few minutes or without much hassle, it may not hurt to ask. There are times, though, when it helps to let things go or put a pin in them:

- If you ask for many small changes and some get missed, ask yourself if there’s time for the author to clean up anything left over. If not, try to let it go.

- If you encounter a conflict of code style but no standard* has been set, let it go. Asking for a change in this state could result in reverting it once a standard has been set.

- Sometimes, medium-sized changes, e.g., refactoring a solution, don’t need to happen right away. In these cases, take the time to document what needs to be done and see if you can schedule it as soon as possible.

* Automate Your Standards

As much as possible, automate your code standards. If possible, document the reasons behind them. This saves tons of time talking about the standards and also saves time teaching them.

It may seem like a lot of work up front but I’ve seen too many cases of long-lived teams paying the cost of not standardizing early, even to the point of crippling themselves and delaying the shipment of every feature.

A note on standards: I feel fairly confident that some standard is far better than no standard but watch out for choosing standards that can be hard to change later.

Improving my own feedback has saved me a lot of time over the years and helped me build better relationships with PR authors, even those with whom I don’t frequently interact. Hopefully, you can also apply some of these suggestions to your own PR feedback and see good results.